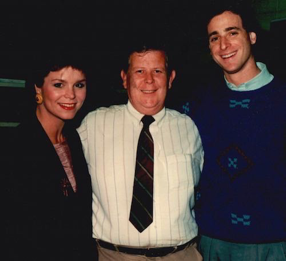

Frank Heying (center) with Liz Matt and former student Bob Saget.

Frank Heying taught me everything I know about film editing. I'll never forget the first day of his class. Frank proclaimed himself to be the instructor at Temple University who failed the most students. He went on to say that our first editing assignment would require fifty hours of work outside the classroom on our own time. He strongly advised anyone who couldn't handle that workload throughout the entire semester to drop the course. There were at least thirty students in the classroom that first day. For the second class, that number was cut in half. I remember looking around at all the empty seats. I was ready for the challenge and driven by Frank’s expectations.

The first assignment was to edit a scene from the old television show Gunsmoke. Frank was not kidding about the fifty hours of work and I definitely put in more than that. He gave us the raw footage on actual reels of black and white film along with a razor and splicer for editing. We used a machine called a Steenbeck that played the reels through a monitor and speakers.

This was my introduction to the movie slate. For those experienced with film, my description of this process will seem obvious, but I can’t remember how many times I had to explain this to friends and family. Since the picture and sound were separate, the first thing I had to do was put them in sync. First, I found the frame where the movie slate was completely closed. Next, I listened to the audio and located the frame where I heard the sound of the clap. I lined the picture and audio up, locked the Steenbeck and the scene played in sync. This had to be done for every single angle and take. The film had numbers on the edge of the frames, so once everything was in sync, I wrote the corresponding numbers on the audio track to keep things organized while I edited.

I watched the footage dozens of times and took notes on the best takes. Once I had a rough edit of the footage in my head, I cut up the film and spliced it together. If I didn't like my edit, I peeled off the tape and tried a different version. The frames were the size of a fingernail, so it was very easy to misplace one. If I decided to use a frame I already discarded, I would have to dig through the bin of individual frames to find it. We had a wall of hooks to hang pieces of unused film and eventually the whole area looked like a spaghetti dinner.

I loved every minute of that class and learned so much from the experience. I asked Frank a lot of questions and he was always encouraging and could tell that I had a genuine interest in film editing. On several occasions, Frank visited me as I worked at the Steenbeck and offered his feedback on my work. Frank was a master at spotting bad edits, especially when switching angles. There are twenty-four frames in each second of film and Frank could tell if your picture and sound were out of sync by just one frame, a skill that I have picked up over the years thanks to him.

I went on to receive an “A” for the project, and also for the class, and each year Frank helped me with the annual American Cinema Editors student competition. I received raw film footage from a popular television show and had to edit together my own scene, similar to Frank’s original Gunsmoke assignment. It gave me the opportunity to edit footage from the shows ER, Law & Order and NYPD Blue. While I never won the competition, each year’s learning experience, combined with Frank’s encouragement, took me to another level as an editor.

When I was in film school, digital editing was a brand new technology. I recall Frank saying that anyone can learn a computer program, not everyone can edit. At the time, Temple had only one computer editing system, not just for all the undergraduates to share, but for the graduate students as well. Time had to be scheduled on it, weeks in advance. There was also a limited amount of hard drive space.

There was an incident where a student deleted files to make room for his own. My entire project mysteriously disappeared. This was around the time the notorious Unabomber was in the news for sending bombs in the mail, so I made a "Who is the Unadeleter?" poster and taped it on the wall over the computer editing system. My creative sign got people talking and I found out who deleted my project files. It was a graduate student and I confronted him in front of my other classmates. No more projects were deleted.

In one of the final assignments for Frank’s class, he gave us footage of a local news report about Friday the 13th. We were allowed to edit it however we wanted as long as we included at least one clip from the news footage. I went above and beyond expectations for this exercise and made a three-minute compilation of horror movie clips edited together as a music video featuring a White Zombie song. Since I worked at the video store, I had access to all the films I wanted. I probably spent about twenty hours getting all the clips, but it was worth it. I later used the same technique to make two other compilation videos. The first was a Star Wars music video set to the song “On the Dark Side” performed by John Cafferty and the Beaver Brown Band.

The second was a tribute to John Hughes using clips from Sixteen Candles, The Breakfast Club and Weird Science edited to a cover of “Don’t You Forget About Me” performed by the band Life of Agony, originally performed by Simple Minds.

Frank was also my instructor for a television production class. Back then, Conan O’Brien was new to late night television and his sidekick was Andy Richter. My uncle Tom had a friend named Michael Shelinok who looked just like Andy Richter. For my final project, Michael came down to the television studio at Temple and filmed a short segment we wrote called The Andy Richter Show.

Temple Film School was the best learning experience of my life, but I was there when the movie industry was making the awkward shift from film to digital. Today’s students have no idea how easy they have it with computerized editing. Just ask Frank Heying.

Grandmom Emery with my daughter on Easter 2011.

During my film school years, I stayed with my grandmother, Betty Emery, and my uncle, Tom Emery, in the Chestnut Hill section of Philadelphia. Grandmom and Tom both looked after me like I was one of their own. Not only did Grandmom give me motherly advice, she listened to every one of my movie ideas and watched all of my film school projects. We had many Scrabble tournaments, which I always won of course, but only because she had a habit of selecting vowels from the letter bag, or at least that’s what she said. I often joked that Grandmom got me to watch the five o’clock news, the five-thirty news, the six o’clock news and the six-thirty news. That was followed by Jeopardy and Wheel of Fortune, and later that night, the eleven o’clock news and then Nightline. I could have done without the constant newsfeed, but there’s one show Grandmom got me to watch that I never would have discovered on my own: Columbo, the detective series starring Peter Falk. Grandmom loved her mysteries.

Living with my uncle Tom was also quite an experience. Tom had a strange combination of clumsiness and bad luck. Who else would have three separate flat tires in one weekend? Who else would break his leg while trying to climb a pile of snow? The best was when I was talking to him at the kitchen table and noticed he was missing a lens in his glasses. When I told him, he reached his finger in to check and ended up poking his eye. But for every funny Tom story, there are countless ones where Tom also treated me like a son. Just like Grandmom, Tom looked out for me while I was going to college. He taught me how to ride the Philadelphia bus, train and subway systems while showing me around the city.

In 1994, Tom joined me on a five-day trip to Hollywood, California. We stayed at a hotel on Sunset Boulevard within walking distance to the Walk of Fame where I took lots of pictures of the names and handprints. We went to Universal Studios and saw every major Hollywood landmark along with some random celebrity sightings, including Weird Al Yankovic on Venice Beach.

One night, while wandering the Walk of Fame, smoke poured out of a bus that was parked across the street. It looked like it was on fire and a crowd gathered. Suddenly, a red carpet and celebrities appeared. The bus was a prop for the premiere of the movie Speed starring Keanu Reeves and Sandra Bullock. I took photos of Edward Furlong, Jane Seymour, Dermot Mulroney, Eric Stoltz and many others.

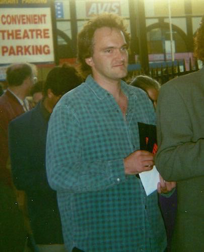

There was one celebrity that nobody recognized, but I did. He was the writer/director of an independent film called Reservoir Dogs. He just filmed Pulp Fiction. It wasn’t publicly released yet, but already won the Palme D’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. Yes, Quentin Tarantino was standing in line right in front of me. I snapped a picture and was about to congratulate him on his award for Pulp Fiction, but the line started to move again. I always replay that moment in my head and wish I had said something. Since he was somewhat under the radar at the time, there’s a chance he might have remembered me.

I took this pic of Quentin Tarantino at the premiere for Speed in 1994.

Tom and I also visited the nightclub The Viper Room. It was owned by Johnny Depp and it was less than a year since River Phoenix died of a drug overdose on the sidewalk outside. We got there early to make sure we got in and the whole night was a surreal experience. I remember seeing actor Esai Morales as soon as we walked through the door. I recognized him from the movie La Bamba and Tom talked to him at the bar later that night. The club was packed beyond capacity and we stayed until closing. There is a scene in my script The Breathing Sequel that is inspired by my visit to The Viper Room.

Grandmom Emery passed away on July 17, 2011. I’m always thankful that she got a chance to meet my daughter. Tom passed away while I was writing this book on June 4, 2014.

This is the last known picture of Tom, taken on Easter 2014.